Across the globe, phosphogypsum, or PG, — a byproduct created during the phosphate manufacturing process — is used to help farmers grow crops, replant forests, and even create artificial reefs and oyster beds to support aquatic life.

But in the United States, most PG has been generally stored in gypstacks, heavily regulated structures that can reach up to 500 feet tall and span acres. On Oct. 9, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) conditionally approved the use of PG in a pilot road project at Mosaic’s New Wales facility in Florida, granting us the opportunity to catch up to our global competitors and work toward sustainable economic growth.

“We want people to know this is a safe and worthwhile resource, not a waste, and we are decades behind others who long ago realized just that,” said Sarah Fedorchuk, Mosaic Vice President — Government and Public Affairs.

The journey to this test project began decades ago, before the knowledge we have today allowed us to understand the scope of putting what was thought to be waste to work.

Why Do We Use Gypstacks, Anyway?

In the 1980s, gypstacks were thought to be the safest way to store PG due to risk of radioactivity. However, advances in science and technology have shown us that PG only has the presence of Naturally Occurring Radioactive Materials, often called NORM. NORM poses a very low risk to public safety, and you likely encounter it in your daily life. It can be found in everyday items including granite countertops, fluorescent lightbulbs, watches, smoke detectors and even cat litter. In fact, the NORM found in PG falls well below the EPA’s risk threshold.

While considered the safest option at the time, the creation of gypstacks decades ago did not account for storing PG long-term, or the significant amounts of PG produced over time. For every ton of phosphate used, three to five tons of PG are produced and then stored. After stacks close, they can require up to 50 years of additional maintenance and regulatory review, costing valuable time and money. In Florida, 21 gypstacks are at capacity.

Catching up with our global competitors means finding new, innovative ways to use PG instead of stacking it — starting with our pilot road project.

What’s Happening with the PG Pilot Road Project?

Prior to obtaining EPA conditional approval, a study at the University of Florida was conducted on sustainable road materials. Acting as an absorbent material when mixed with water, PG is an ideal substitute for helping to prevent road decay over time. Now, the EPA has approved a pilot road project allowing for a 3,200-foot test at our New Wales facility. Following the EPA’s conditional approval, a 30-day public comment period also began on Oct. 9.

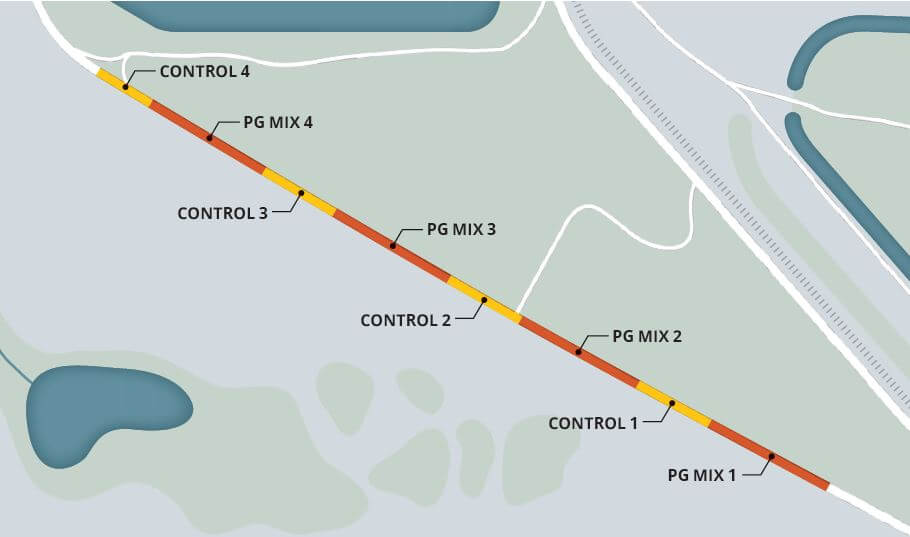

The pilot road, located fully on our property and several miles away from the public, will be divided into eight sections and use several different materials as a road base. Four of the sections will be controls, using existing road materials. The remaining four sections will be mixes of PG with other common road materials, each adjacent to a control section. Each section and its environmental impacts will undergo review as part of the study.

The pilot road will be located at the New Wales property, using PG from the New Wales gypstack.

PG will be located beneath the surface as part of an experimental road base.

This base will be 10 inches deep, located under 3 inches of asphalt pavement. In total, approximately 1,200 tons of PG will be used in the study. The road will take one month to build and will be monitored for at least 18 months.

Mosaic has taken several safety measures prior to the start of this project, including studying hydraulic conditions and obtaining soil samples.

In 2023, the Tampa Bay Times editorial board didn’t dismiss the idea of PG reuse by writing: “The more constructive approach is to proceed cautiously toward answering three questions: ‘Is it safe, is it less risky than what we are doing now, and is it better than other alternatives?’”

In the conditional approval earlier this month, the EPA said in a statement, “Mosaic’s risk assessment is technically acceptable and indicates that the potential radiological risks from the proposed project meet the regulatory requirements of 40 CFR 61.206; that is, the project poses no greater radiological risk than maintaining the phosphogypsum in a stack.”

With more than 20 countries recycling 40 million tons of PG annually for over 55 uses, we look forward to this opportunity at testing PG as a road base in our road.

“At the end of the day, we welcome robust testing,” Fedorchuk said. “PG has value in the right circumstances, and we expect the results of the trial road to reflect that.”

Jan. 2025 Update

In a column published Jan. 16, 2025, in the Tampa Bay Times, Opinion Editor Graham Brink wrote that the use of PG in a test road could prove to be “a good thing,” citing the EPA’s extensive analysis of the pilot road project, along with the monitoring that will be done by researchers from the University of Florida.

“Many of life’s big decisions require measuring risks. In this case, we should not let a natural but often overblown fear of radiation skew the calculation. This road is a sensible and well-controlled test,” writes Brink.

To read the full column, click here.